INTRODUCTION

The landscape of dentistry is changing, and the topic of airways has been influencing dentistry rapidly. Besides the historical aspects of dentistry, such as preventative, restorative, periodontics, and orthodontics, there are new players in the game. Dental sleep medicine, oral appliance therapy, and integrative medicine are infiltrating the dynamics of dentistry. More so, there is an urgent need for integrative dentistry, which encompasses collaboration, technology, and referrals and is creating a paradigm shift. As a general dentist who became a junkie for all types of CE, I stumbled upon dental sleep medicine after more than 20 years in private practice. It all started when my youngest son, Gabriel, didn’t speak so clearly at age 4. Breastfeeding was a struggle for me as a working mother, and the triad of asthma, eczema, and allergies was commonplace among all my 3 children. That was the start of my passion and journey as a clinician in integrative dentistry. Today, our practice, although it has been primarily a restorative practice, started shifting toward airway and dental sleep medicine because I felt there was a benefit to treating my dental patients through the lens of airway and collaborative treatment.

As a general dentist, I am keenly aware of the crucial role that a healthy airway plays in maintaining optimal oral health. The airway is responsible for the passage of air from the outside environment to the lungs, allowing for proper respiration and oxygenation of the body. Its significance extends beyond respiratory functions, directly impacting oral health, dental development, and overall well-being. In fact, many patients have medical conditions that make a regular hygiene visit secondary. This calls for the need to look at patients, no matter their age, from a different perspective. Understanding how the medical conditions of our dental patients can play a significant role in assessing their dental conditions is crucial and warranted in our treatment planning. Some have sleep apnea, undiagnosed sleep-related breathing disorders, Down syndrome, TMJ issues, autoimmune disorders, movement disorders, autism, ADHD, and speech issues, to name several.

CASE REPORTS

Case 1

Then came Julian, a sweet 4-year-old boy whose mother found me because her last option was to have her son undergo tonsils and adenoid surgery based on the advice of a local ENT doctor. She was searching for alternative options even though medicating her 4-year-old son with daily montelukast and Flonase was not helping that much. Julian still wore pull-ups at night and was struggling with bed-wetting. He had a medical history of asthma, was breastfed for 2 years, and had latching problems.

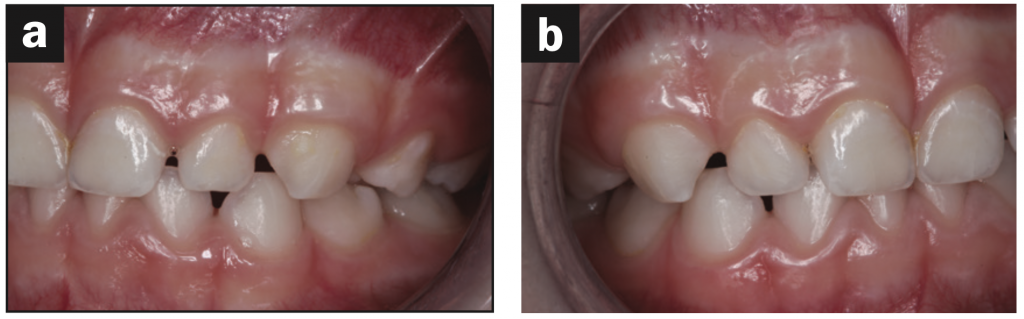

Based on the protocol in our office, and after performing a clinical exam, I requested an assessment by a speech-language pathologist. She evaluated him and recommended myofunctional therapy, and together we devised a strategy to change his growth trajectory and look for ways to decrease inflammation in his body. I recommended a nutritionist and a consultation with a sleep physician. A picture template was taken, and the following dental exam findings were shared with all providers involved in his care (Figures 1 to 3).

The goals of myofunctional therapy for a 4-month time frame were listed as the following:

1. Breathing re-education to maximize nasal breathing capacity

2. Lingual stretches and maximizing normal range of motion

3. Increase lingual stability and symmetrical movement

4. Improve lip function

5. Teaching correct oral postures for rest, swallowing, and speech

6. Eliminate tongue thrust on swallowing for saliva, liquids, semi-solid textures, and solid textures

7. Articulation therapy (speech- and language-based)

The treatment between all providers included the following:

1. Myofunctional therapy to correct tongue thrust, reverse swallow, and low tongue posture

2. A functional appliance during bedtime and incorporating diaphragmatic breathing exercises to promote more nasal breathing

3. Eliminating sugar from the diet and testing for ferritin levels at a later date.

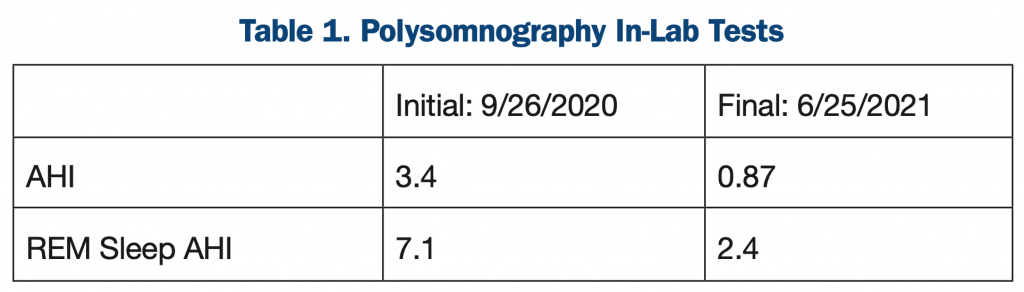

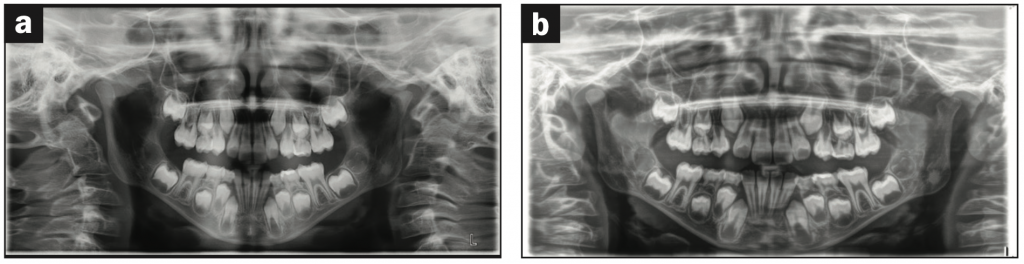

His original polysomnography (PSG) sleep test came back positive for sleep apnea with an AHI of 3.4. The ENT initial examination resulted in a recommendation of adenoid and tonsil removal and a follow-up post-PSG sleep study. We started myofunctional therapy right away and saw Julian monthly for 5 months. His initial presentation of a narrow arch and vaulted palate contributed to his mouth breathing habit. The tongue tie and reverse swallow contributed to the tongue thrusting and weak tongue function. After 6 months of functional appliance therapy—and, in his case, using a pre-ortho appliance—he began to sleep better with the appliance in place for the next year.

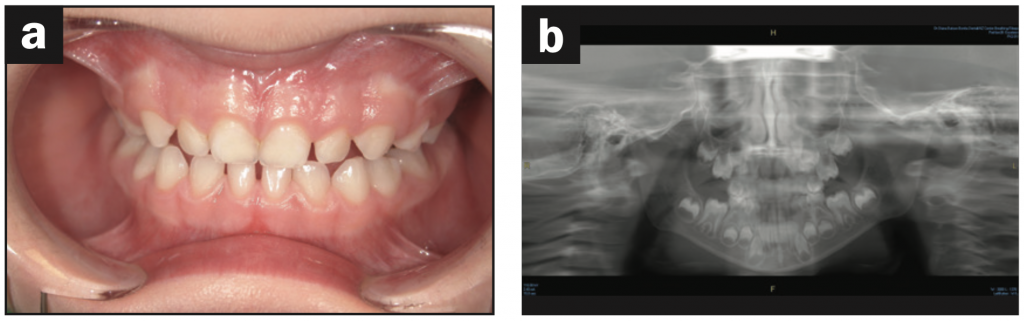

His follow-up ENT appointment, which was one year later, concluded that surgery was no longer necessary, and his sleeping pattern improved. His original apnea/hypopnea index improved from 3.4 to 0.87 (Table 1). The ultimate result was that he no longer exhibited signs of sleep apnea. The final recommendation from my office was to continue to use the appliance nightly during bedtime and evaluate the patient in 8 months to one year to determine if maxillary expansion would be an option. From a dental perspective, addressing the oral habits and correcting the mouth breathing promoted nasal breathing and increased the space for permanent teeth eruption. Myofunctional therapy successfully improved the mouth breathing and tongue-thrusting habits (Figure 4).

Case 2

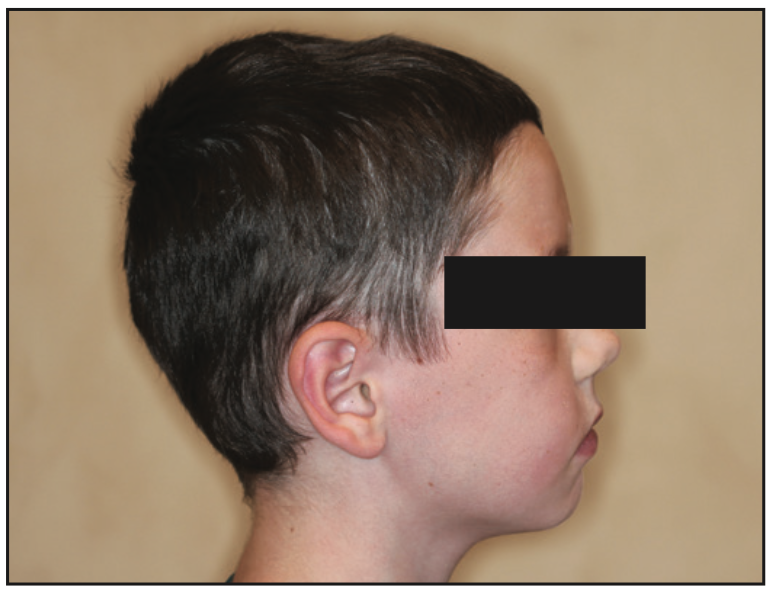

Eric was a 7-year-old child referred by a local sleep physician. The sleep physician relied on my expertise to see how airway dentistry could benefit Eric simultaneously with his CPAP protocol. His medical history included past adenoid and tonsil removal surgery and no prior orthodontic history. Because we discussed how dentistry can be a favorable strategy in growth and development of the face, the sleep physician was well aware of our practice’s capabilities. We discussed the option of interceptive orthodontics because children who already wear a CPAP often present an issue with compliance. The type of expanders and timing of insertion needs to be planned. Because the full-face mask can cause a mid-face deficiency, the bonded rapid palatal expander could fail or result in less-than-optimal results. The first question I asked Eric was, “If we could find a way to wean you off your CPAP and help you sleep better at night, would you want to try that strategy?” His eyes lit up, and he was high-fiving me at the end of the appointment. He just wanted to feel better every day and maybe even attend a regular school. His mom was homeschooling at this point. He talked about the possibility of attending a summer camp if he did not have to bring his machine with him. When I met Eric for the first time, he was 7, and his initial sleep apnea lab test resulted in AHI of 11.2. (Parameters for pediatric sleep apnea are more sensitive than adult parameters. Therefore any value of apnea/hypopnea index greater than 1 is considered to be relevant according to the International Classification of Sleep Disorders guidelines (ICSD-3-TR). His central apneas were 17, and his respiratory index was 11.2. During the in-lab PSG, he showed evidence of moderate sleep apnea, sleep bruxism, and possible restless leg syndrome. In addition, he demonstrated nocturnal enuresis (Figures 5 to 8).

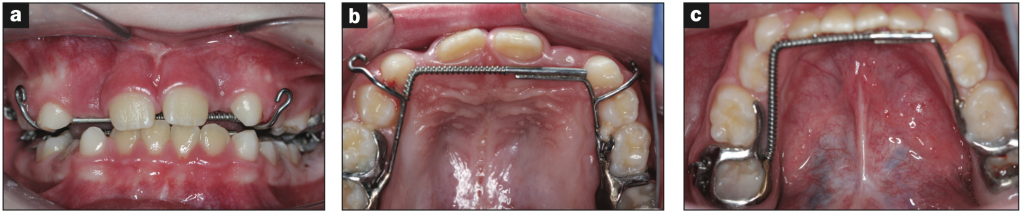

He was originally fitted with a full-face CPAP, and the sleep physician consulted with me to see if we could start the maxillary expansion. We started with a functional appliance (pre-ortho) to be worn at night, and he started myofunctional therapy. The sleep physician then switched him to a nasal cannula and kept the pressure the same. Meanwhile, I performed a tongue-tie release using a CO2 laser (LightScalpel) in conjunction with myofunctional therapy. His initial CPAP pressure was 4 cm H2O. From a craniofacial profile and development picture, the following was observed: mid-face deficiency, low tongue posture, narrow arches, and a posterior tongue-tie. After just 6 months of expansion using upper and lower E-arches (Motor City Lab Works in Birmingham, Mich), his mom reported improvement in behavior, sleep patterns, and bed-wetting (Figure 9).

Figure 9. (a) Expansion with E-arches. (b) Upper occlusal with E-arch. (c) Lower occlusal with E-arch.

Sometimes when doing collaborative treatment with the sleep physician, we may do a follow-up sleep study to evaluate progress. However, because Eric was on CPAP treatment, we were able to download data from his machine. His current data from the CPAP recordings show an AHI of 2.1. The next plan is to do a final PSG and see if changes in CPAP and/or pressure are recommended. The sleep physician and I agreed that maxillary expansion with the E-arches and myofunctional therapy was beneficial for the patient. Releasing his posterior tongue-tie alongside myofunctional therapy promoted improved nasal breathing and corrected oral habits such as thrusting and malocclusion of his lower anterior teeth.

Case 3

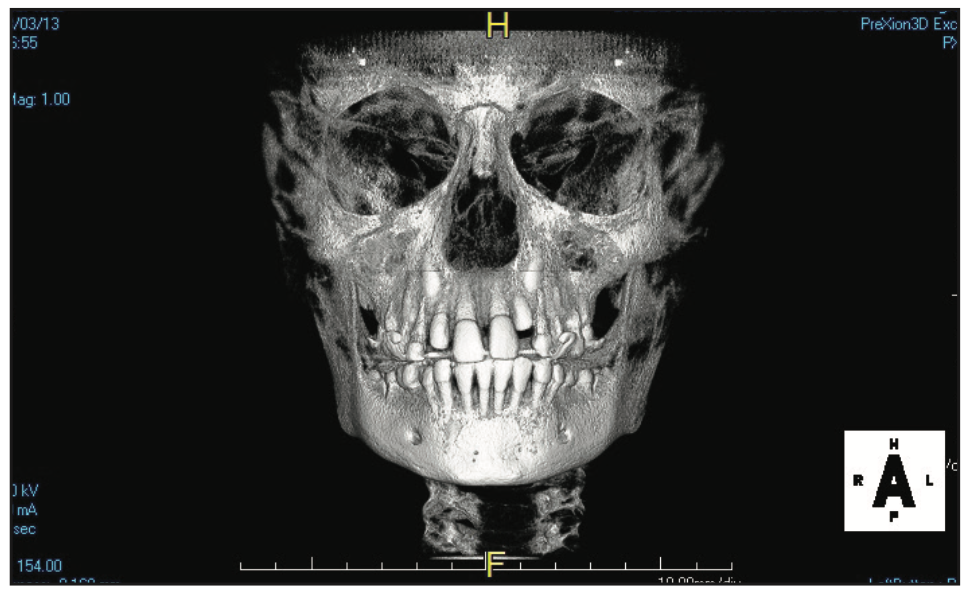

Preston was a referral from a colleague close by. He had a history of prior orthodontic expansion and was dealing with anxiety and poor sleep patterns. He had a tongue-tie release as a baby, and his mom stated she had difficulty nursing. A previous consultation with a new dental provider recommended extractions of permanent teeth Nos. 5, 12, 21, and 28. Preston’s mother was against the recommendations and explored other options. She was referred to my practice by her dentist (Figures 10, 11a, and 12a).

Preston’s treatment plan among all providers included the following:

1. Implementation of myofunctional therapy and lingual frenectomy

2. Upper maxillary expansion with bonded RPE

3. Continuing with first-phase aligner therapy using ClearCorrect aligners

4. Frenuloplasty revision using a LightScalpel CO2 laser

5. Continued myofunctional therapy for 6 to 8 more months

6. Checking ferritin levels and assessing improvement of anxiety levels

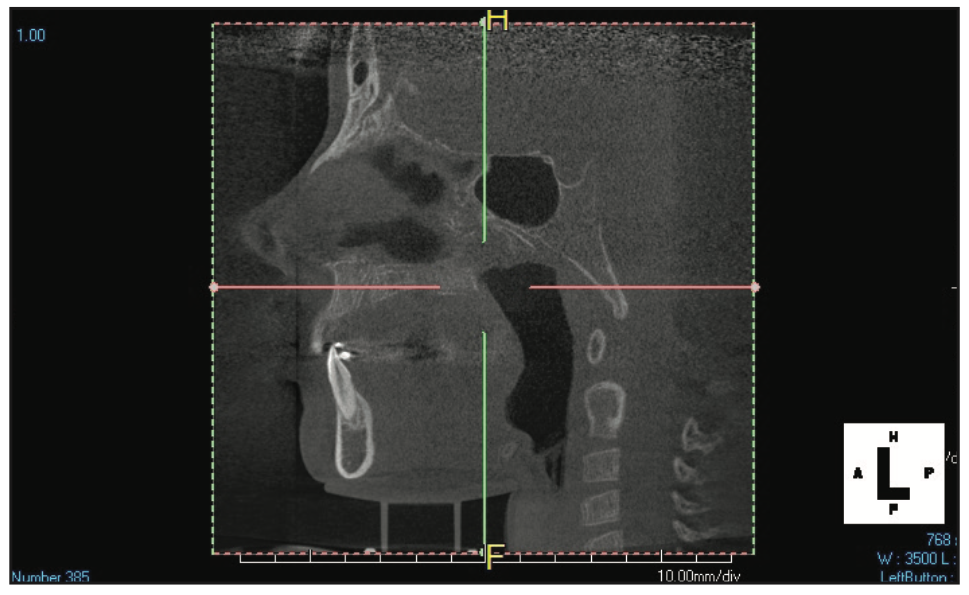

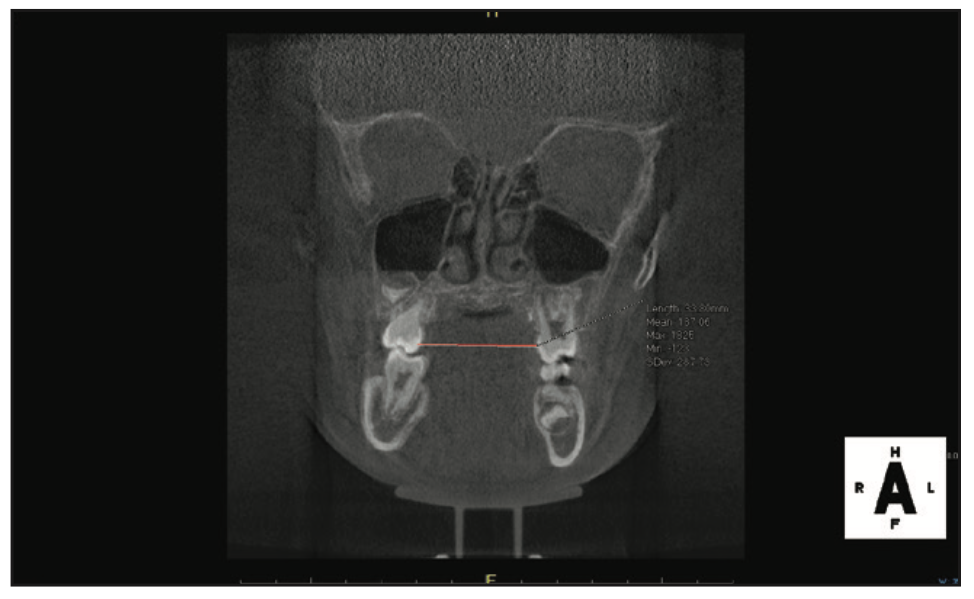

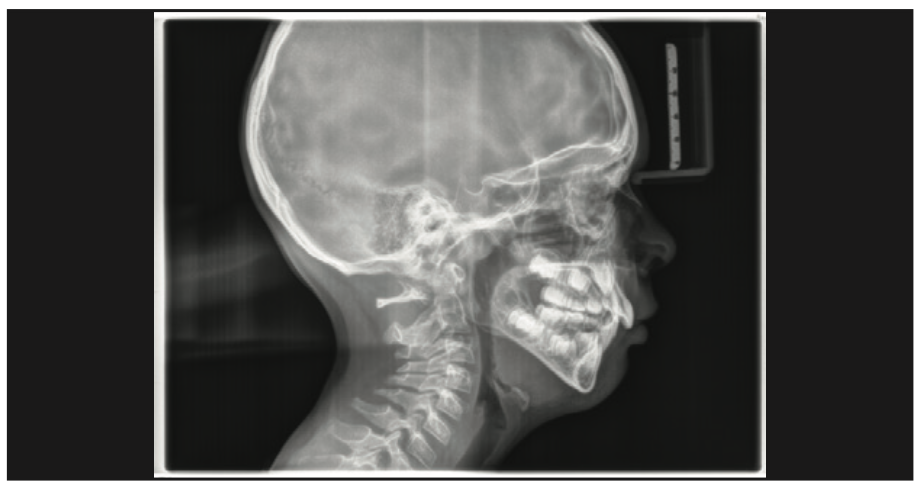

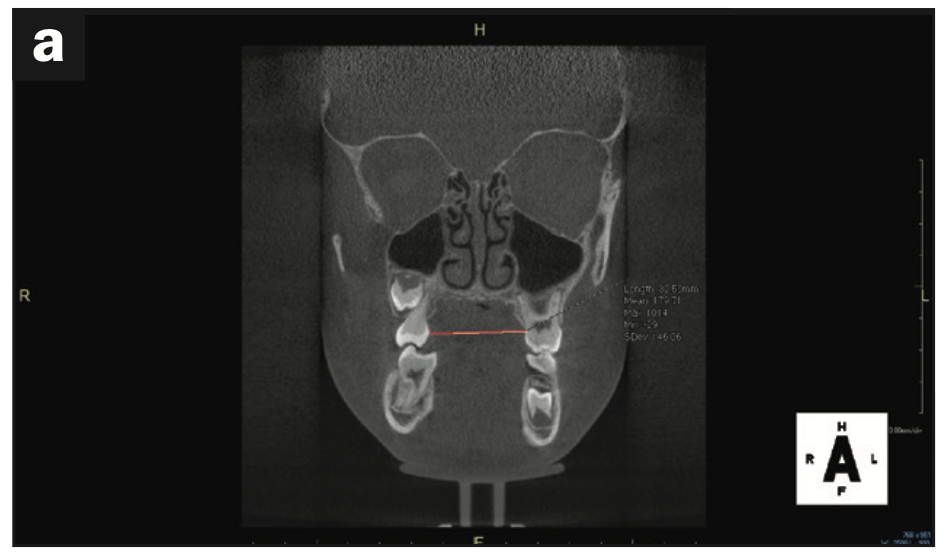

Regarding treatment planning, an airway strategy was implemented. In this case, we used CBCT technology (3D Excelsior PRO [PreXion]) to preplan interceptive orthodontic treatment using a rapid, bonded palatal expander. In just 6 months, his maxillary intermolar width improved, the space for all bicuspid teeth was present, and no extractions were necessary. Initial measurements of the maxillary intermolar width from teeth Nos. 3 to 14 was 30 mm. Progress maxillary intermolar width improved to 36 mm. He is currently in upper bonded RPE and lower clear aligners (ClearCorrect). Tongue space and function were enhanced, thus increasing the chance for nasal breathing. Other improvements included overbite, overjet, and arch form. His future treatment will consist of a possible second phase of clear aligners once growth is complete (Figures 11 to 13).

Figure 12. (a) Initial frontal photo. (b) Progress frontal photo. (c) Before lingual frenectomy. (d) After lingual frenectomy.

DISCUSSION

There are 3 important signs of a restricted airway:

1. Cessation of breathing

2. Excessive daytime sleepiness

3. Snoring

It’s important to know what the signs of a healthy airway are. Here are some things to consider.

1. Unobstructed nasal passages: The concept of healthy breathing allows airflow that decreases the effects of bacteria. Nasal congestion or blockages due to allergies, sinus issues, or anatomical abnormalities can impact breathing and disrupt the balance of the airway.

2. Proper jaw development: The development of a well-aligned and properly developed jaw can significantly contribute to a healthy airway. This concept can be identified at a young age. When the upper and lower jaws are in harmony, there is adequate space for the tongue, which prevents it from falling back and obstructing the airway during sleep.

3. A well-positioned tongue: The tongue plays a crucial role in maintaining an open airway. It should rest against the roof of the mouth, supporting the upper jaw and maximizing the space available for breathing. A healthy airway allows the tongue to maintain this position effortlessly. Lip seal and facial muscle strength and control are all contributing factors.

4. Adequate tonsil size: Tonsils are part of the lymphatic system and are located at the back of the throat. They act as a defense mechanism against infections. When the tonsils become enlarged or inflamed, they can obstruct the airway and contribute to breathing difficulties. In the presence of inflammation, their sizes will vary.

5. Efficient breathing patterns: Healthy breathing involves smooth, effortless inhalation and exhalation. It should be predominantly nasal breathing, which filters and humidifies the air, promoting optimal lung function and oxygen exchange.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, a healthy airway is a fundamental component of good oral health. Proper breathing patterns, nasal breathing, and the prevention and treatment of conditions like sleep apnea are key factors in maintaining optimal oral health throughout a person’s life. When dentistry can be a part of the answer and treatment options for our patients, we are better healthcare providers. There are different strategies and treatment plans we can offer our patients with possible sleep-related breathing disorders. Myofunctional therapy, tongue-tie release, and even nutritional counseling paired with interceptive orthodontics can change the trajectory of the child during his or her growth and development years. Some cases may involve or warrant the consultation of an ENT surgeon or sleep physician. In our practice, when we involve multiple disciplines into the treatment planning phase, we help healthcare providers become open to possibilities and integrate learning from each other. This can support the chance of effective treatment, especially if they have a diagnosis of sleep apnea. Because growth and development are still occurring, there is time to improve the trajectory. By educating our patients, their families, and other healthcare providers about the importance of a healthy airway and offering appropriate interventions, we can contribute to their overall wellness and provide the comprehensive dental care they deserve.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Dr. Batoon is an industry leader and champion for airway in dentistry. She received her doctorate from Tufts University School of Dental Medicine. Her expertise and passion for education has helped build her private practice in Scottsdale, Ariz. She is a Diplomate of the American Board of Dental Sleep Medicine and actively participates in research for sleep apnea for both adults and children. She has contributed to dental journals, podcasts, and blogs and is an international speaker on oral health and airways. Because of her own experiences with her 3 boys, she is passionate about helping babies, children, and adults to promote a healthy airway through sleep, myofunctional therapy, laser dentistry, and interceptive orthodontics. She can be reached at azsleepwellness@gmail.com.

Disclosure: Dr. Batoon is a clinical educator for Glidewell Labs and New West Lab and lectures for Candid Aligners and PreXion.