INTRODUCTION: WHAT EVERY DENTIST SHOULD KNOW

Even if you don’t place dermal fillers, every dentist should be aware of filler complications that can manifest in the oral cavity. In fact, when a patient presents with unexplained intraoral tissue slough or necrosis with a recent history of dermal filler treatment, vascular compromise should be included as a differential diagnosis. It is well-established that filler vascular events respond best to early intervention, and the correct diagnosis is the first step in achieving an optimum outcome.1 The dentist is poised to play a pivotal role in recognizing these potential vascular events, thereby initiating the proper treatment trajectory and averting permanent damage.

A report published in the Journal of Dermatologic Surgery details a case of gingival necrosis following dermal filler treatment in the nasal area.2 We will examine the case history, covering its presentation, initial diagnosis, and outcome. A map of the embolic pathway that likely caused the gingival necrosis will provide a deeper understanding of the mechanics in play.

Dermal filler treatments consistently rank in the top 5 minimally invasive procedures performed annually and continue to trend upward from pre-pandemic levels.3 It should not be surprising that adverse events have kept pace commensurately with this rise in annual treatments. Overall, these treatments are well-tolerated, with most complications being mild and self-limiting. The majority of filler-associated adverse events manifest extraorally and are observed locally on the facial skin. As with all embolic events, early recognition and treatment are key to avoiding morbidity. Knowledgeable dental practitioners who are aware of these less common adverse events can make the difference between irreversible necrosis and full recovery.

VASCULAR ANATOMY OVERVIEW

Recognizing manifestations of a filler-induced vascular occlusion (FIVO) requires only 2 skills. The first is general knowledge of orofacial vascular connections, and the second is a healthy degree of suspicion regarding diagnostic approaches. Similar to other pathologies that dentists are trained to recognize, treatment of the pathology is not required of a consulting dentist. Appropriate and timely referrals are the only obligation.

The facial blood supply is largely provided by the facial artery and its branches (Figure 1). This artery is a branch of the external carotid. Generally speaking, early evidence of an evolving FIVO is most often detected by localized skin blanching in the immediate and/or adjacent areas.

Figure 1. Facial blood supply.

The internal carotid artery mainly supplies the brain and eyes and is, therefore, less commonly involved in FIVOs. However, there are multiple areas where the internal and external carotid blood supplies are indirectly comingled (Figure 2). The potential for intracranial involvement in filler vascular events is real and well-documented. Moreover, there are several physiologically intentional vascular connections that provide a direct union between these distinct blood sources. The head and neck are replete with examples of redundant “backup” systems between internal and external carotid blood sources, as well as redundancies between major branches of the facial artery. These “vascular repeats” contribute to the body’s ability to respond to changes and challenges. Unfortunately, these connections are also capable of allowing potentially problematic downstream effects to manifest. Embolic events can present in unexpected areas that may be distant from the injection site.

Figure 2. Internal and external carotid blood supplies.

CASE HISTORY

A 42-year-old female presented to a facial plastic surgeon seeking cosmetic changes to the appearance of her nose. The surgeon placed dermal filler in the nasal spine area. A day after the procedure, the patient developed intraoral symptoms, which she did not associate with the dermal filler treatment. The patient sought dental evaluation and treatment. The dentist observed gingival necrosis in the maxillary area of tooth No. 8, extending superiorly to and including the mucobuccal fold of the ipsilateral lip and extending laterally to include the gingival marginal crest of tooth No. 7. The dental diagnosis was presumed to be of gingival etiology. The dentist placed the patient on daily topical chlorhexidine. A week later, the intraoral necrosis was assumed to be a FIVO. An exophytic palatal lesion was also identified at that time. The surgeon administered hyaluronidase injections adjacent to the nasal spine to dissolve the hyaluronic acid dermal filler at that visit. The patient was placed on antibiotic therapy as well as antiplatelet drugs and corticosteroids for necrotic tissue management and infection prevention. Subsequent hyaluronidase injections were also delivered. Four days after the final hyaluronidase injections, the appearance of the gingivae and mucosa were improved. Fourteen days later, the tissue demonstrated complete resolution.

INTRAORAL VASCULAR OCCLUSION MECHANISM

In the case presented, the patient received dermal filler in the nasal spine area. Arterial supply to the anterior nose and nasal spine area is furnished largely by branches of the superior labial artery. The gingiva, papilla, and labial mucosa in the contiguous intraoral aesthetic zone are also supplied by the superior labial artery and its branches. Conversely, the bone and periosteum deep into this area are supplied by the infraorbital artery.4 This explains why the soft tissues suffered necrosis while the hard tissues in the same zone were spared. Distal to the area of involvement, beginning with the premolars and areas posterior, the soft tissues are supplied by the middle superior alveolar artery and the posterior superior alveolar artery, respectively.

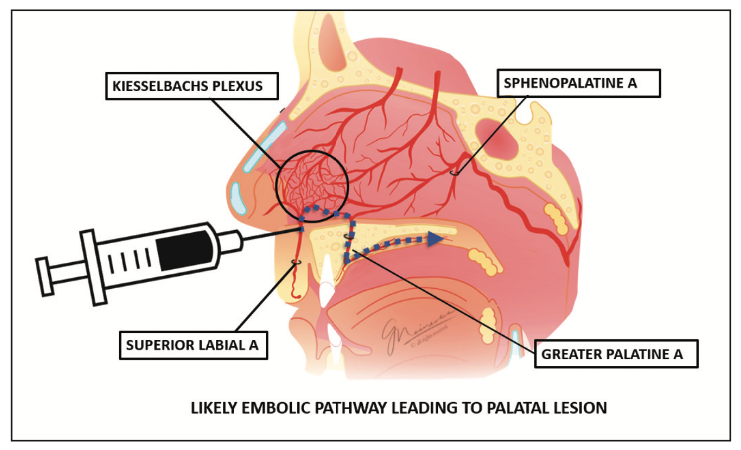

The palatal lesion can likewise be explained by the same embolic event. The superior labial artery is a branch of the facial artery that courses along the upper lip. It gives off several branches that enter the nasal cavity, supplying blood to the area of the nasal septum as well as the ala of the nose. These branches ramify in the nasal cavity, where they anastomose with terminal arteries from both the internal and external carotid arteries in an area named the Kiesselbach’s plexus.

The hard palate and its overlying mucosa receive blood supply primarily from the greater palatine artery. The dense network of vasculature of the Kiesselbach’s plexus allows connection between the sphenopalatine artery and the greater palatine artery as it enters the nasal cavity via the incisive foramen. The most likely cause of the patient’s palatal lesion was due to an embolic event traveling from the superior labial artery to the greater palatine artery (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Cause of the patient’s palatal lesion.

CONCLUSION

The oral cavity is teeming with vascular connections linking facial arterial branches servicing the skin with those that supply hard and soft tissues of the mouth. It’s known that filler particles can travel with blood flow downstream until the diameter of the vessel becomes too narrow to allow passage of the embolus, resulting in a blockage.5 However, it is also established that, with injection pressure, filler can travel retrogradely, following any number of anastomotic pathways, to ultimately occlude distant vessels under the transport and direction of blood pressure and flow.6

Reports of intraoral vascular occlusions occurring after dermal filler injections are, fortunately, less common than those manifesting on the facial skin. However, reports in the literature involving the gingivae, palate, tongue, and oral mucosa continue to emerge. Regrettably, patients often fail to make the connection between the dermal filler procedure and the intraoral symptomatology. These patients may self-refer to a dentist. It is not necessary for the practitioner to be trained in the delivery of facial injectables to make the correct differential diagnosis and proper referral. When a patient presents with an intraoral slough or necrosis, the history should include a line of questioning pertaining to recent dermal filler treatment. This is sufficient to rule a FIVO in or out as a possible etiology.

REFERENCES

- King M, Walker L, Convery C, et al. Management of a vascular occlusion associated with cosmetic injections. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2020;13(1):E53-E58.

- Rauso R, Bove P, Rugge L, et al. Unusual intraoral necrosis after hyaluronic acid injections. Dermatol Surg. 2021;47(8):1158–60. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000003099

- American Society of Plastic Surgeons. 2022 ASPS Procedural Statistics Release: 2022 Minimally invasive procedures.

- Shahbazi A, Feigl G, Sculean A, et al. Vascular survey of the maxillary vestibule and gingiva-clinical impact on incision and flap design in periodontal and implant surgeries. Clin Oral Investig.2021;25(2):539–46. doi:10.1007/s00784-020-03419-w

- DeLorenzi C. Complications of injectable fillers, part 2: vascular complications. Aesthet Surg J. 2014;34(4):584-600. doi:10.1177/1090820X14525035

- Rzany B, DeLorenzi C. Understanding, avoiding, and managing severe filler complications. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2015;136(5 Suppl):196S-203S. doi:10.1097/PRS.0000000000001760

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Dr. Meinecke has been teaching injectables nationally since 2004. She is the facial injectable program director at the Boston University School of Dental Medicine and a pro-sector in head and neck anatomy and provides litigation support in the form of expert witness within the injectable domain. She has written for numerous publications and is the author of the book Start and Grow Your Cosmetic Injectable Practice. Dr. Meinecke maintains a private practice limited to facial injectables in Potomac, Md. She can be reached at meinecke@bu.edu.

Disclosure: Dr. Meinecke reports no disclosures.